30

A Comprehensive Guide To Error Handling In Node.js

This article was originally written by Ayooluwa Isaiah on the Honeybadger Developer Blog.

If you've been writing anything more than "Hello world" programs, you are probably familiar with the concept of errors in programming. They are mistakes in your code, often referred to as "bugs", that cause a program to fail or behave unexpectedly. Unlike some languages, such as Go and Rust, where you are forced to interact with potential errors every step of the way, it's possible to get by without a coherent error handling strategy in JavaScript and Node.js.

It doesn't have to be this way, though, because Node.js error handling can be quite straightforward once you are familiar with the patterns used to create, deliver, and handle potential errors. This article aims to introduce you to these patterns so that you can make your programs more robust by ensuring that you’ll discover potential errors and handle them appropriately before deploying your application to production!

An error in Node.js is any instance of the

Error object. Common examples include built-in error classes, such as ReferenceError, RangeError, TypeError, URIError, EvalError, and SyntaxError. User-defined errors can also be created by extending the base Error object, a built-in error class, or another custom error. When creating errors in this manner, you should pass a message string that describes the error. This message can be accessed through the message property on the object. The Error object also contains a name and a stack property that indicate the name of the error and the point in the code at which it is created, respectively.const userError = new TypeError("Something happened!");

console.log(userError.name); // TypeError

console.log(userError.message); // Something happened!

console.log(userError.stack);

/*TypeError: Something happened!

at Object.<anonymous> (/home/ayo/dev/demo/main.js:2:19)

<truncated for brevity>

at node:internal/main/run_main_module:17:47 */Once you have an

Error object, you can pass it to a function or return it from a function. You can also throw it, which causes the Error object to become an exception. Once you throw an error, it bubbles up the stack until it is caught somewhere. If you fail to catch it, it becomes an uncaught exception, which may cause your application to crash!The appropriate way to deliver errors from a JavaScript function varies depending on whether the function performs a synchronous or asynchronous operation. In this section, I'll detail four common patterns for delivering errors from a function in a Node.js application.

The most common way for functions to deliver errors is by throwing them. When you throw an error, it becomes an exception and needs to be caught somewhere up the stack using a

try/catch block. If the error is allowed to bubble up the stack without being caught, it becomes an uncaughtException, which causes the application to exit prematurely. For example, the built-in JSON.parse() method throws an error if its string argument is not a valid JSON object.function parseJSON(data) {

return JSON.parse(data);

}

try {

const result = parseJSON('A string');

} catch (err) {

console.log(err.message); // Unexpected token A in JSON at position 0

}To utilize this pattern in your functions, all you need to do is add the

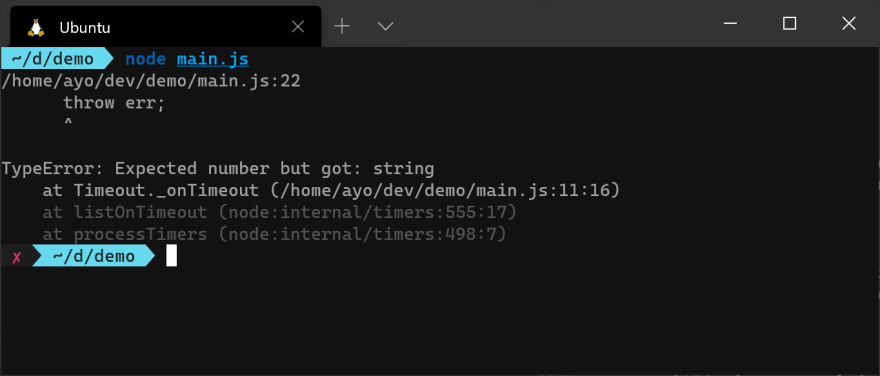

throw keyword before an instance of an error. This pattern of error reporting and handling is idiomatic for functions that perform synchronous operations.function square(num) {

if (typeof num !== 'number') {

throw new TypeError(`Expected number but got: ${typeof num}`);

}

return num * num;

}

try {

square('8');

} catch (err) {

console.log(err.message); // Expected number but got: string

}Due to its asynchronous nature, Node.js makes heavy use of callback functions for much of its error handling. A callback function is passed as an argument to another function and executed when the function has finished its work. If you've written JavaScript code for any length of time, you probably know that the callback pattern is heavily used throughout JavaScript code.

Node.js uses an error-first callback convention in most of its asynchronous methods to ensure that errors are checked properly before the results of an operation are used. This callback function is usually the last argument to the function that initiates an asynchronous operation, and it is called once when an error occurs or a result is available from the operation. Its signature is shown below:

function (err, result) {}The first argument is reserved for the error object. If an error occurs in the course of the asynchronous operation, it will be available via the

err argument and result will be undefined. However, if no error occurs, err will be null or undefined, and result will contain the expected result of the operation. This pattern can be demonstrated by reading the contents of a file using the built-in fs.readFile() method:const fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('/path/to/file.txt', (err, result) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

return;

}

// Log the file contents if no error

console.log(result);

});As you can see, the

readFile() method expects a callback function as its last argument, which adheres to the error-first function signature discussed earlier. In this scenario, the result argument contains the contents of the file read if no error occurs. Otherwise, it is undefined, and the err argument is populated with an error object containing information about the problem (e.g., file not found or insufficient permissions).Generally, methods that utilize this callback pattern for error delivery cannot know how important the error they produce is to your application. It could be severe or trivial. Instead of deciding for itself, the error is sent up for you to handle. It is important to control the flow of the contents of the callback function by always checking for an error before attempting to access the result of the operation. Ignoring errors is unsafe, and you should not trust the contents of

result before checking for errors.If you want to use this error-first callback pattern in your own async functions, all you need to do is accept a function as the last argument and call it in the manner shown below:

function square(num, callback) {

if (typeof callback !== 'function') {

throw new TypeError(`Callback must be a function. Got: ${typeof callback}`);

}

// simulate async operation

setTimeout(() => {

if (typeof num !== 'number') {

// if an error occurs, it is passed as the first argument to the callback

callback(new TypeError(`Expected number but got: ${typeof num}`));

return;

}

const result = num * num;

// callback is invoked after the operation completes with the result

callback(null, result);

}, 100);

}Any caller of this

square function would need to pass a callback function to access its result or error. Note that a runtime exception will occur if the callback argument is not a function.square('8', (err, result) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err)

return

}

console.log(result);

});You don't have to handle the error in the callback function directly. You can propagate it up the stack by passing it to a different callback, but make sure not to throw an exception from within the function because it won't be caught, even if you surround the code in a

try/catch block. An asynchronous exception is not catchable because the surrounding try/catch block exits before the callback is executed. Therefore, the exception will propagate to the top of the stack, causing your application to crash unless a handler has been registered for process.on('uncaughtException'), which will be discussed later.try {

square('8', (err, result) => {

if (err) {

throw err; // not recommended

}

console.log(result);

});

} catch (err) {

// This won't work

console.error("Caught error: ", err);

}

Promises are the modern way to perform asynchronous operations in Node.js and are now generally preferred to callbacks because this approach has a better flow that matches the way we analyze programs, especially with the

async/await pattern. Any Node.js API that utilizes error-first callbacks for asynchronous error handling can be converted to promises using the built-in util.promisify() method. For example, here's how the fs.readFile() method can be made to utilize promises:const fs = require('fs');

const util = require('util');

const readFile = util.promisify(fs.readFile);The

readFile variable is a promisified version of fs.readFile() in which promise rejections are used to report errors. These errors can be caught by chaining a catch method, as shown below:readFile('/path/to/file.txt')

.then((result) => console.log(result))

.catch((err) => console.error(err));You can also use promisified APIs in an

async function, such as the one shown below. This is the predominant way to use promises in modern JavaScript because the code reads like synchronous code, and the familiar try/catch mechanism can be used to handle errors. It is important to use await before the asynchronous method so that the promise is settled (fulfilled or rejected) before the function resumes its execution. If the promise rejects, the await expression throws the rejected value, which is subsequently caught in a surrounding catch block.(async function callReadFile() {

try {

const result = await readFile('/path/to/file.txt');

console.log(result);

} catch (err) {

console.error(err);

}

})();You can utilize promises in your asynchronous functions by returning a promise from the function and placing the function code in the promise callback. If there's an error,

reject with an Error object. Otherwise, resolve the promise with the result so that it's accessible in the chained .then method or directly as the value of the async function when using async/await.function square(num) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

if (typeof num !== 'number') {

reject(new TypeError(`Expected number but got: ${typeof num}`));

}

const result = num * num;

resolve(result);

}, 100);

});

}

square('8')

.then((result) => console.log(result))

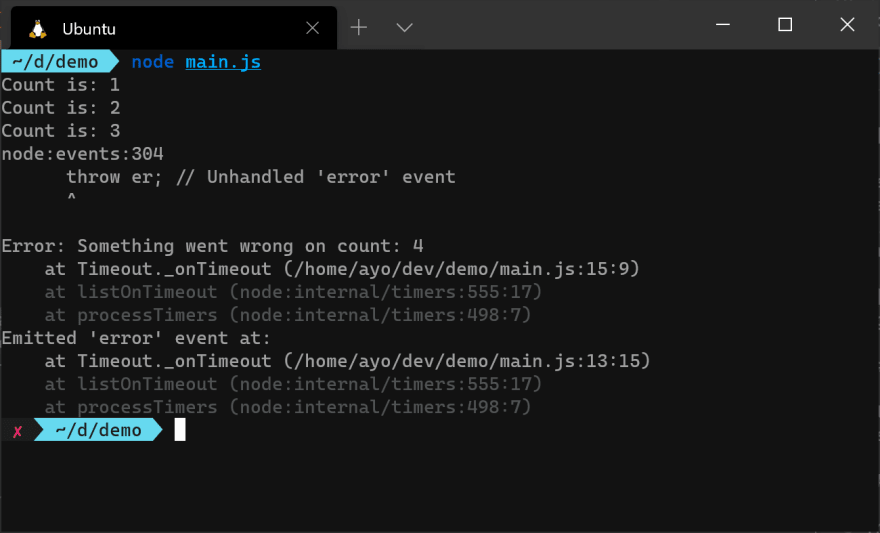

.catch((err) => console.error(err));Another pattern that can be used when dealing with long-running asynchronous operations that may produce multiple errors or results is to return an EventEmitter from the function and emit an event for both the success and failure cases. An example of this code is shown below:

const { EventEmitter } = require('events');

function emitCount() {

const emitter = new EventEmitter();

let count = 0;

// Async operation

const interval = setInterval(() => {

count++;

if (count % 4 == 0) {

emitter.emit(

'error',

new Error(`Something went wrong on count: ${count}`)

);

return;

}

emitter.emit('success', count);

if (count === 10) {

clearInterval(interval);

emitter.emit('end');

}

}, 1000);

return emitter;

}The

emitCount() function returns a new event emitter that reports both success and failure events in the asynchronous operation. The function increments the count variable and emits a success event every second and an error event if count is divisible by 4. When count reaches 10, an end event is emitted. This pattern allows the streaming of results as they arrive instead of waiting until the entire operation is completed.Here's how you can listen and react to each of the events emitted from the

emitCount() function:const counter = emitCount();

counter.on('success', (count) => {

console.log(`Count is: ${count}`);

});

counter.on('error', (err) => {

console.error(err.message);

});

counter.on('end', () => {

console.info('Counter has ended');

});

As you can see from the image above, the callback function for each event listener is executed independently as soon as the event is emitted. The

error event is a special case in Node.js because, if there is no listener for it, the Node.js process will crash. You can comment out the error event listener above and run the program to see what happens.

Using the built-in error classes or a generic instance of the

Error object is usually not precise enough to communicate all the different error types. Therefore, it is necessary to create custom error classes to better reflect the types of errors that could occur in your application. For example, you could have a ValidationError class for errors that occur while validating user input, DatabaseError class for database operations, TimeoutError for operations that elapse their assigned timeouts, and so on.Custom error classes that extend the

Error object will retain the basic error properties, such as message, name, and stack, but they can also have properties of their own. For example, a ValidationError can be enhanced by adding meaningful properties, such as the portion of the input that caused the error. Essentially, you should include enough information for the error handler to properly handle the error or construct its own error messages.Here's how to extend the built-in

Error object in Node.js:class ApplicationError extends Error {

constructor(message) {

super(message);

// name is set to the name of the class

this.name = this.constructor.name;

}

}

class ValidationError extends ApplicationError {

constructor(message, cause) {

super(message);

this.cause = cause

}

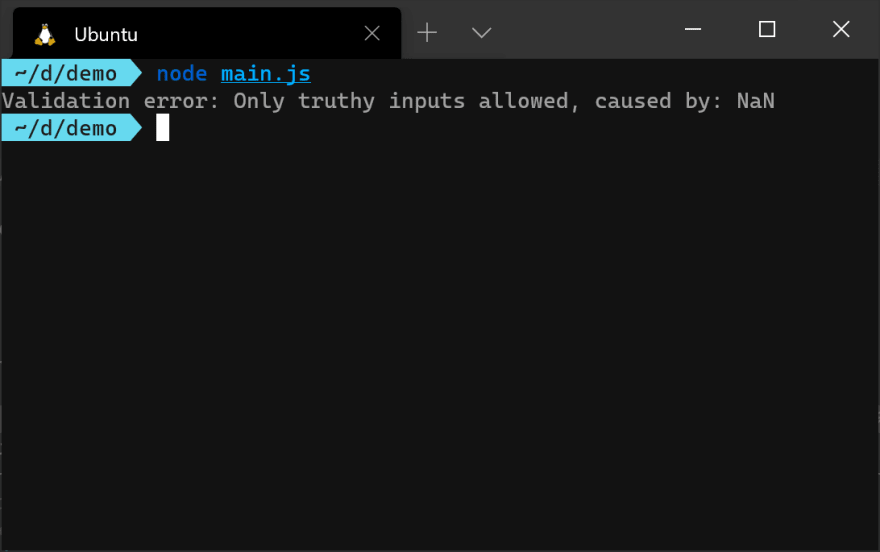

}The

ApplicationError class above is a generic error for the application, while the ValidationError class represents any error that occurs when validating user input. It inherits from the ApplicationError class and augments it with a cause property to specify the input that triggered the error. You can use custom errors in your code just like you would with a normal error. For example, you can throw it:function validateInput(input) {

if (!input) {

throw new ValidationError('Only truthy inputs allowed', input);

}

return input;

}

try {

validateInput(userJson);

} catch (err) {

if (err instanceof ValidationError) {

console.error(`Validation error: ${err.message}, caused by: ${err.cause}`);

return;

}

console.error(`Other error: ${err.message}`);

}

The

instanceof keyword should be used to check for the specific error type, as shown above. Don't use the name of the error to check for the type, as in err.name === 'ValidationError', because it won't work if the error is derived from a subclass of ValidationError.It is beneficial to distinguish between the different types of errors that can occur in a Node.js application. Generally, errors can be siloed into two main categories: programmer mistakes and operational problems. Bad or incorrect arguments to a function is an example of the first kind of problem, while transient failures when dealing with external APIs are firmly in the second category.

Operational errors are mostly expected errors that can occur in the course of application execution. They are not necessarily bugs but are external circumstances that can disrupt the flow of program execution. In such cases, the full impact of the error can be understood and handled appropriately. Some examples of operational errors in Node.js include the following:

These situations do not arise due to mistakes in the application code, but they must be handled correctly. Otherwise, they could cause more serious problems.

Programmer errors are mistakes in the logic or syntax of the program that can only be corrected by changing the source code. These types of errors cannot be handled because, by definition, they are bugs in the program. Some examples of programmer errors include:

Operational errors are mostly predictable, so they must be anticipated and accounted for during the development process. Essentially, handling these types of errors involves considering whether an operation could fail, why it might fail, and what should happen if it does. Let's consider a few strategies for handling operational errors in Node.js.

In many cases, the appropriate action is to stop the flow of the program's execution, clean up any unfinished processes, and report the error up the stack so that it can be handled appropriately. This is often the correct way to address the error when the function where it occurred is further down the stack such that it does not have enough information to handle the error directly. Reporting the error can be done through any of the error delivery methods discussed earlier in this article.

Network requests to external services may sometimes fail, even if the request is completely valid. This may be due to a transient failure, which can occur if there is a network failure or server overload. Such issues are usually ephemeral, so instead of reporting the error immediately, you can retry the request a few times until it succeeds or until the maximum amount of retries is reached. The first consideration is determining whether it's appropriate to retry the request. For example, if the initial response HTTP status code is 500, 503, or 429, it might be advantageous to retry the request after a short delay.

You can check whether the Retry-After HTTP header is present in the response. This header indicates the exact amount of time to wait before making a follow-up request. If the

Retry-After header does not exist, you need to delay the follow-up request and progressively increase the delay for each consecutive retry. This is known as the exponential back-off strategy. You also need to decide the maximum delay interval and how many times to retry the request before giving up. At that point, you should inform the caller that the target service is unavailable.When dealing with external input from users, it should be assumed that the input is bad by default. Therefore, the first thing to do before starting any processes is to validate the input and report any mistakes to the user promptly so that it can be corrected and resent. When delivering client errors, make sure to include all the information that the client needs to construct an error message that makes sense to the user.

In the case of unrecoverable system errors, the only reasonable course of action is to log the error and terminate the program immediately. You might not even be able to shut down the server gracefully if the exception is unrecoverable at the JavaScript layer. At that point, a sysadmin may be required to look into the issue and fix it before the program can start again.

Due to their nature, programmer errors cannot be handled; they are bugs in the program that arise due to broken code or logic, which must subsequently be corrected. However, there are a few things you can do to greatly reduce the frequency at which they occur in your application.

When you migrate your entire project over to TypeScript, errors like "

undefined is not a function", syntax errors, or reference errors should no longer exist in your codebase. Thankfully, this is not as daunting as it sounds. Migrating your entire Node.js application to TypeScript can be done incrementally so that you can start reaping the rewards immediately in crucial parts of the codebase. You can also adopt a tool like ts-migrate if you intend to perform the migration in one go.Many programmer errors result from passing bad parameters. These might be due not only to obvious mistakes, such as passing a string instead of a number, but also to subtle mistakes, such as when a function argument is of the correct type but outside the range of what the function can handle. When the program is running and the function is called that way, it might fail silently and produce a wrong value, such as

NaN. When the failure is eventually noticed (usually after traveling through several other functions), it might be difficult to locate its origins.You can deal with bad parameters by defining their behavior either by throwing an error or returning a special value, such as

null, undefined, or -1, when the problem can be handled locally. The former is the approach used by JSON.parse(), which throws a SyntaxError exception if the string to parse is not valid JSON, while the string.indexOf() method is an example of the latter. Whichever you choose, make sure to document how the function deals with errors so that the caller knows what to expect.On its own, the JavaScript language doesn't do much to help you find mistakes in the logic of your program, so you have to run the program to determine whether it works as expected. The presence of an automated test suite makes it far more likely that you will spot and fix various programmer errors, especially logic errors. They are also helpful in ascertaining how a function deals with atypical values. Using a testing framework, such as Jest or Mocha, is a good way to get started with unit testing your Node.js applications.

Uncaught exceptions and unhandled promise rejections are caused by programmer errors resulting from the failure to catch a thrown exception and a promise rejection, respectively. The

uncaughtException event is emitted when an exception thrown somewhere in the application is not caught before it reaches the event loop. If an uncaught exception is detected, the application will crash immediately, but you can add a handler for this event to override this behavior. Indeed, many people use this as a last resort way to swallow the error so that the application can continue running as if nothing happened:// unsafe

process.on('uncaughtException', (err) => {

console.error(err);

});However, this is an incorrect use of this event because the presence of an uncaught exception indicates that the application is in an undefined state. Therefore, attempting to resume normally without recovering from the error is considered unsafe and could lead to further problems, such as memory leaks and hanging sockets. The appropriate use of the

uncaughtException handler is to clean up any allocated resources, close connections, and log the error for later assessment before exiting the process.// better

process.on('uncaughtException', (err) => {

Honeybadger.notify(error); // log the error in a permanent storage

// attempt a gracefully shutdown

server.close(() => {

process.exit(1); // then exit

});

// If a graceful shutdown is not achieved after 1 second,

// shut down the process completely

setTimeout(() => {

process.abort(); // exit immediately and generate a core dump file

}, 1000).unref()

});Similarly, the

unhandledRejection event is emitted when a rejected promise is not handled with a catch block. Unlike uncaughtException, these events do not cause the application to crash immediately. However, unhandled promise rejections have been deprecated and may terminate the process immediately in a future Node.js release. You can keep track of unhandled promise rejections through an unhandledRejection event listener, as shown below:process.on('unhandledRejection', (reason, promise) => {

Honeybadger.notify({

message: 'Unhandled promise rejection',

params: {

promise,

reason,

},

});

server.close(() => {

process.exit(1);

});

setTimeout(() => {

process.abort();

}, 1000).unref()

});You should always run your servers using a process manager that will automatically restart them in the event of a crash. A common one is PM2, but you also have

systemd or upstart on Linux, and Docker users can use its restart policy. Once this is in place, reliable service will be restored almost instantly, and you'll still have the details of the uncaught exception so that it can be investigated and corrected promptly. You can go further by running more than one process and employ a load balancer to distribute incoming requests. This will help to prevent downtime in case one of the instances is lost temporarily.No error handling strategy is complete without a robust logging strategy for your running application. When a failure occurs, it's important to learn why it happened by logging as much information as possible about the problem. Centralizing these logs makes it easy to get full visibility into your application. You'll be able to sort and filter your errors, see top problems, and subscribe to alerts to get notified of new errors.

Use

npm to install the package:$ npm install @honeybadger-io/js --saveImport the library and configure it with your API key to begin reporting errors:

const Honeybadger = require('@honeybadger-io/js');

Honeybadger.configure({

apiKey: '[ YOUR API KEY HERE ]'

});You can report an error by calling the

notify() method, as shown in the following example:try {

// ...error producing code

} catch(error) {

Honeybadger.notify(error);

}For more information on how Honeybadger integrates with Node.js web frameworks, see the full documentation or check out the sample Node.js/Express application on GitHub.

The

Error class (or a subclass) should always be used to communicate errors in your code. Technically, you can throw anything in JavaScript, not just Error objects, but this is not recommended since it greatly reduces the usefulness of the error and makes error handling error prone. By consistently using Error objects, you can reliably expect to access error.message or error.stack in places where the errors are being handled or logged. You can even augment the error class with other useful properties relevant to the context in which the error occurred.Operational errors are unavoidable and should be accounted for in any correct program. Most of the time, a recoverable error strategy should be employed so that the program can continue running smoothly. However, if the error is severe enough, it might be appropriate to terminate the program and restart it. Try to shut down gracefully if such situations arise so that the program can start up again in a clean state.

Programmer errors cannot be handled or recovered from, but they can be mitigated with an automated test suite and static typing tools. When writing a function, define the behavior for bad parameters and act appropriately once detected. Allow the program to crash if an

uncaughtException or unhandledRejection is detected. Don't try to recover from such errors!Use an error monitoring service, such as Honeybadger, to capture and analyze your errors. This can help you drastically improve the speed of debugging and resolution.

Proper error handling is a non-negotiable requirement if you're aiming to write good and reliable software. By employing the techniques described in this article, you will be well on your way to doing just that.

Thanks for reading, and happy coding!

30